RE:DEFINING Normal: A Prescription for a Canadian Cultural Landscape in Recovery

Valerie Sing Turner for Culture Days

Aug 16, 2021

Let’s transform our grief into anger—because it is anger that motivates us to act. Let’s marshal our anger into action for the good of our sector and our communities.

Many Canadians, artists included, long to return to normal—especially now as theatres, concert halls, cinemas, studios, museums, galleries, and other venues that provide arts and cultural experiences slowly but tentatively welcome back in-person gatherings. But for Indigenous and racialized artists, “normal” has never been an option in the Canadian cultural landscape. As we approach the end of our second summer of a global pandemic, this is a fantastic opportunity for us to consider how we might redefine normal.

Like Toto pulling back the curtain to reveal the truth behind the Wizard of Oz, COVID-19 peeled back the synthetic veneer of normalcy to expose widespread and egregious systemic inequality, particularly the twin plagues of systemic racism and white supremacy. The stories and the stats are disheartening: anti-Blackness is alive and well in our country; the UK-based The Guardian named Vancouver the “anti-Asian hate crime capital of North America” following a mind-boggling 700% increase in police reports; and the recent mass murder of a Muslim family is but the latest outrageous act of unchecked Islamophobia in Canada.

More recently, the horrifying truth of genocide on Canadian soil following the discovery of the remains of hundreds of Indigenous children in unmarked graves on the grounds of multiple residential schools has many non-Indigenous people finally questioning the colonial roots of Canada Day—having overlooked the fact that for nearly a century, some Chinese-Canadian communities mark the holiday as “Humiliation Day”, ever since the Chinese Exclusion Act banning Chinese immigration was enacted on July 1, 1923.

Normalizing the dehumanization of people because of their race, gender, religion, sexuality, or disability is, well, not normal. It’s frankly toxic. (And to be fair, it’s not just white folx who are guilty of this; bigotry and discrimination exist among communities of colour as well.) Personally, as an East Asian multidisciplinary artist, I’m well aware of the phenomenon of the Interchangeable Asian — though in my play, In the Shadow of the Mountains, one character puts it more succinctly: “You know, it’s a fallacy that Asians look alike. What that person really is saying is that they don’t give a shit enough to really see you.” As the past year’s events have demonstrated, the normal too many yearn for is deadly for far too many.

While we mourn in solidarity with Indigenous artists and communities across Turtle Island, and with all communities touched by the injustices of this year and beyond, it’s too easy to wallow in sadness, and indulge in helplessness and paralysis—or worse, performative and pious virtue-signalling. Instead, let’s transform our grief into anger—because it is anger that motivates us to act. Let’s marshal our anger into action for the good of our sector and our communities.

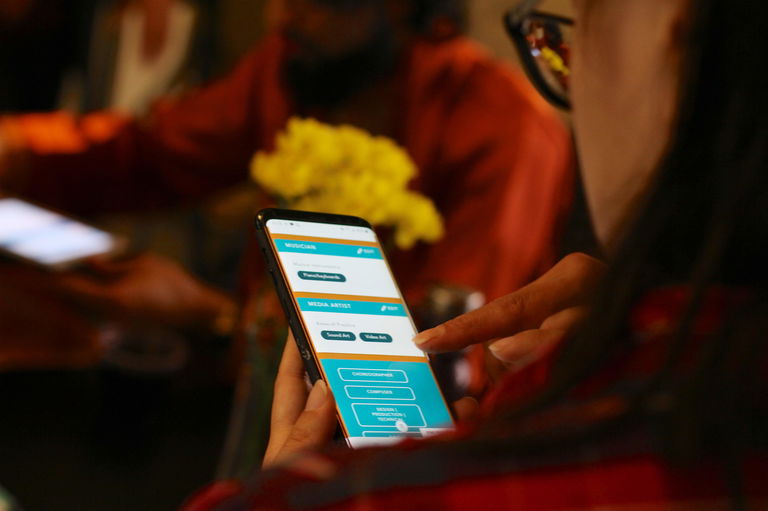

For Visceral Visions, the multidisciplinary arts company I founded 18 years ago, the cycle of transforming grief into anger into action has been an ongoing process of redefining normal for the past decade. Over the last five years, we’ve been developing CultureBrew.Art (CBA), a digital platform that features a searchable national database of Indigenous and racialized artists. While the growing number of databases of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) working in screen-based media are much-needed additions to the cause, CBA is the only platform thus far to also include artists in the performing and literary arts, acknowledging the reality that so many of us work across multiple disciplines. CBA was conceived to push back against the myth that the lack of diverse representation in the faces and stories onstage and onscreen is due to a perplexing inability to find us, along with the fallacy that because we’re “hard to find”, we therefore don’t exist.

Built and developed by racialized artists for POC artists, the site is intercultural, interdisciplinary, and intersectional in the way we embrace and make space for the multiplicity of identity and lived experience that informs the work of Indigenous and racialized artists.

By seeking to build connection, collaboration, and community among racialized artists, CBA centres artists of colour rather than serving white power structures. While these values already make CultureBrew.Art unique, we are also far-reaching in our vision for CBA to benefit communities beyond the arts.

The work of racialized artists can disrupt systemic racism in other sectors of civil society, from education (working with students in schools and post-secondary training programs as faculty and guest artists), community and social service agencies (working with immigrants, refugees, POC queer youth, and other marginalized groups), to government (arts advisories, funding juries), media outlets, ad agencies, and more!

In addition to searching directly for artists, anyone wanting to promote a call for artists, job positions, or notices about awards and funding programs, can easily post an opportunity on the site. This summer, we were especially excited to be working with a racialized team of grad students as part of an Industry Project Partnership with the Centre for Digital Media, developing a CBA mobile app prototype equipped with a geolocator that will allow racialized artists in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities to more easily connect—a kind of Tinder for POC artists.

One aspect of working in the digital space we hadn’t fully appreciated before embarking on this journey is that because racialized Canadians are three times more likely to be targeted by online hate, ensuring the privacy and safety of the artists in the CultureBrew.Art community is a significant concern. We have therefore had to invest (and continue to invest) considerable time, protocols, and resources to mitigate digital risks, ranging from identity theft, to trolls and cyber hacks. Despite claims to the contrary, technology is neither objective nor neutral—and more often than not, perpetuates or even exacerbates current oppressive systems.

Finally, we envision the long-term outcome of CBA as one beyond numbers and statistics: a complete systemic, mindset-shift in the arts community encompassing gatekeepers, practitioners, and audience members. It will simply be accepted as a truism that, in a multicultural society like Canada, racial diversity and radical inclusion are par for the course; and engaging in a respectful intercultural way that accurately reflects demographic realities will no longer be seen as a “special interest” anomaly, but as a basic professional standard.

More than anything, CultureBrew.Art is meant to facilitate a structural reimagining of how we might collectively redefine the cultural landscape and its operational definition of who belongs, whose stories are important, and who gets to tell our stories.

Like a well-formulated vaccine, the arts have the potential to immunize Canadian society from the worst of what ails us. But acquiring herd immunity from systemic racism and white supremacy requires compassion, persistence, and vigilance—and a willingness to call a plague a plague.

Cover image: Sammy Chien. Photo credit: Cyrus Wu.

This article is part of a special blog series featuring writers and creatives from across Canada (and beyond!) with stories that both highlight and celebrate Culture Days’ 2021 theme, RE:IMAGINE. Explore more stories below.

- The Road Less Travelled: Three artists reimagine success and career by Linh S. Nguyễn

- Arts in Motion by Aaron Rothermund

- Reimagining Public Spaces: The Share-It-Square in Portland, Oregon by Laura Puttkamer

- Refresh: How a Year on Instagram Redefined Artistic Communities by Eva Morrison

- RE:PURPOSE by Mike Green

- Recalibrating: A Look at Opera InReach by Anya Wassenberg

- Reimagine—How the Disability Community Accesses the Arts by Rachel Marks

- Reimagining Community and the Workplace of Theatre by Natércia Napoleão

- Helm Studios flips the for-profit music model to empower artists by Aly Laube

- Curating INUA, Canada’s newest Inuit art exhibit by Carolyn B. Heller

- When Less is More: What Theatre Can Learn From a Year in Slow Motion by Megan Hunt

- RE:ORCHESTRATING Our Future: Advancing Sustainable Development Through the Arts by Ryan Elliot Drew

- Empathy Machines?: Exploring the Relationship between Immersive Art Technologies and Feeling by Jozef Spiteri and Sunita Nigam

- La poésie pour vivre différemment la pandémie par Jérôme Melançon