Listen to the River: An Ode to the Columbia River

Saba Dar for Culture Days

Jul 8, 2020

They know this River will still be here long after we have turned to nuclear dust and blown away, saith the river…

-Beholden: A poem as long as the river, Rita Wong and Fred Wah

Rolling from one valley to another, streaming across coarse contours, sometimes surrendering to the whims of winds and pouring rain, other times cutting through the rock-ribbed plains; rivers have always made the most enchanted neighbourhoods. A river’s ample bosom has cradled pioneering civilizations and nurtured childhood memories. Its panoramic views have kindled weary eyes and inspired grandiose dreams, and through centuries its gentle ripples have concocted timeless fables of love and romance. By the virtue of their romantic allure, rivers have always been a recurring theme in poetry and literature.

While artists have always, liberally and quite blatantly, borrowed from nature; they have also been moved, time and again, to devote their craft to salvage the very landscapes that enriched their imagination. River Relations: A Beholder’s Share of the Columbia River, an artistic investigation by a group of creatives from Emily Carr University of Art and Design (ECUAD), is one such venture that delves into the destruction inflicted upon by the ‘damming and development’ of the Columbia River, in the wake of the renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty.

Rising in the clear waters of the Columbia Lake in B.C. and surging through glaciated Canadian Rocky Mountains, the Columbia River flows through the Kootenay River—the river’s largest tributary on the Canadian divide of the border. It enters the U.S. at the confluence of Pend d’Orielle River in the Washington state, before conclusively disappearing into the Pacific Ocean near Astoria, Oregon. Columbia River is a water wonderland, flowing with ferocious abundance, making it the largest river in North America’s Pacific Northwest region, and a sanctuary for the largest salmon runs in the world.

Modern civilization has turned rivers into economic powerhouses, plugging them with gargantuan concrete structures to harness hydroelectric power and divert water for irrigation. The Columbia River was subjected to a similar fate, transforming its free-flowing bliss into a curse. A violent flooding spell in 1948 that wrecked the Fraser Valley in B.C, Canada, and the town of Vanport in Oregon, U.S. became the impetus for securing a cooperative development between the two countries. The talks sought to regulate water flows and to capitalize on the river’s enormous hydroelectric capacity, finally culminating into a formal Columbia River Treaty (CRT) in 1964. Canada committed to build three water storage reservoirs in exchange for an upfront payment of $64 million in recompense for extending sixty years of flood control to U.S., in addition to receiving one-half of the estimated hydro-power generation benefits to the U.S, on continual basis. Today, CRT is upheld as a successful example of two countries ‘sharing the benefits’ through a collaborative transboundary arrangement. Yet, the ramifications the treaty had on the Indigenous peoples and the river’s salmon reserve have become a despicable addendum to the treaty.

The River Relations’ team scrutinized historical and contemporary images of the Columbia River to understand the evolution of its landscape, outrageously interrupted by dams. The most notable output of the project is the image-text poem, published in the form of a book, entitled ‘Beholden: A poem as long as the river’, composed by Fred Wah, a former Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate and Rita Wong, a poet and an environmental activist.

Wah and Wong travelled the entire river stretch, from Canal Flats in the East Kootenay all the way to Fort Astoria, Oregon as a part of their research for the book. ‘Having lived along the Kootenay River for much of my life I had always felt that the river should be called the Kootenay; that the Columbia was really just a tributary of the Kootenay’, says Wah.

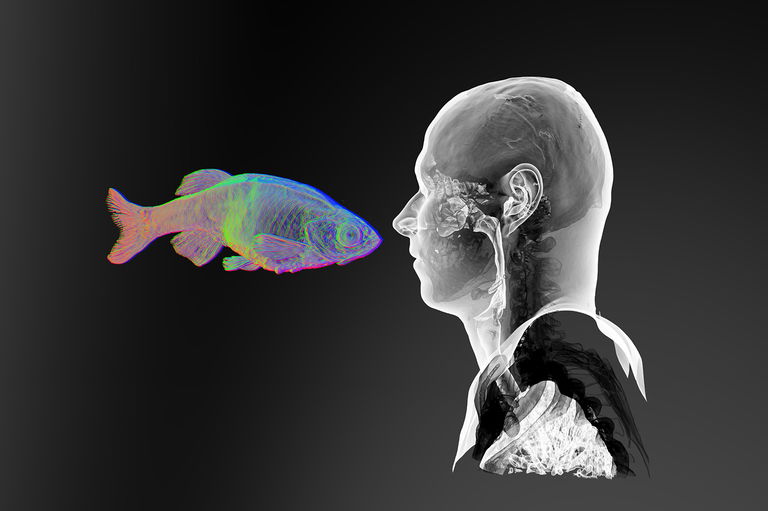

Wah believes that the treaty insolently disregarded the ‘spiritual value’ attributed to the river’s salmon by the First Nations. To them, salmon is the ‘harbinger of good news’, revered as a gift from the salmon king. They believed that the salmon were actually humans, and at the start of each salmon season, they would transform into fish form on the king’s command. They also celebrated the ‘First Salmon Ceremony’ to mark the beginning of each salmon season. Even today, certain tribes celebrate ‘Salmon ceremonies’ with a communal prayer for the salmon to return and inhabit the river again.

The loss of salmon has chronicled a poignant chapter in the river’s history. Wong was swamped with emotions when she watched Upstream Battle (a documentary by Ben Kempas) ‘One moment that always stays with me from that film is footage of salmon trying to swim upstream to return to their spawning grounds - and hitting a dam, and trying over and over to get beyond that obstacle - it’s a heart wrenching glimpse into the painful destruction wrought by megadams.’

Beholden is a reflection on the devastation brought on by the damming of the river and focuses on themes of colonization, indigenous rights and mutilation of the river’s ecology. ‘Most of the language in the poem comes from a struggle between simply describing the river, (..) and finding ways to “listen” to the river’. It was Wah who proposed to write ‘a poem as long as the river’, in collaboration with Wong. ‘With him writing along one side, and me along the other, the words came from our experiences along the river’, Wong reminisces about the poem’s origins. ‘Each of us would write along a shore of the river, from beginning to end, occasionally having our texts cross the river at bridges or dams. Rita’s and my texts were not in conversation as they were written, but, finally, feel tethered to a similar poetic impulse and imagination’ explains Wah.

Just like Wah, Wong also let the river ‘speak to’ her and guide her writing process. ‘Near the headwaters of the river, I made an offering and asked the river for permission to share the words arising from my journeys along it. I listened and keep listening.’

Nick Conbere, a visual artist and an Associate Professor at ECUAD, skillfully transcribed Beholden on a 114 feet long map of the Columbia River, with Wah and Wong’s share of poems meandering along the river, as if two tributaries spiraling the entire stretch of the river. The poem’s two halves are distinctly recognizable, as Wah’s half has been typeset whereas Wong’s is handwritten, a decision she consciously made. ‘I felt it was important to stay with the bodily experience of writing by hand and following the river’s contours. It felt closer to the experiential aspect of being along the river (…)’ While the book was shortlisted for the B.C Book Prize, the poem’s winding digital image has been showcased at numerous art exhibitions.

As the two countries renegotiate the Treaty, uncertainty abounds. Would the revision of the Treaty offer a second chance at reviving all that is lost? Only time can tell. Wong reminds us ‘There are ways to use the land that help to regenerate or heal it … (the way) Indigenous peoples coexisted with what was here - taking care of it rather than exhausting it’.

Today, many artists romanticize nature as well as assume an advocate’s mantle. Wong believes one way the artists can solicit support for environmental issues is by dwelling on ‘how to heal our relations with the land and water’, and by imploring the society ‘to actually care about this’.

The project has drawn to a close, and the artists have moved on to explore further avenues of nature advocacy. For as long as there is heartache for all that has been lost, I’ll quote Wah;

Let’s reach for solace of water to find some deep pool of larger memory that will float us past Savage Island.

This article is part of a special blog series featuring writers and creatives from across Canada with stories that both highlight and celebrate Culture Days’ 2020 theme of Unexpected Intersections. Explore more intersections below:

- Theatre x Sport: Until the Lights Go Out by Taylor Basso

- Indigenous Storytelling x Digital Media: “People are Finally Listening”–Indigenous Animation Rises Up by Chris Robinson

- Academia x Creativity: Building 21: Make zines, not research papers by Greta Rainbow

- Teahouse x Activism: Chinatown’s Living Room: The gathering place for a budding activist community by Anto Chan

- Traditional Craftsmanship x Youth Outreach: At the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, They Build More Than Boats by Aleen Leigh Stanton

- Visual Arts x Science: What happens when you mix an artist, a scientist and a very bright light? by Vivian Orr

- Book Clubs x Digital Landscapes: Strangers and Fiction by Anne Logan